Wednesday, May 20, 2009

New Column on ESPN.com

Who plays the Toughest Minutes?

"Big-Minute Men: Who are teams putting on the ice in the key moments of the game? Who are the centers taking the key draws? Who are the defensive pairings in the final minute of a one-goal game?"

"Big-Minute Men: Who are teams putting on the ice in the key moments of the game? Who are the centers taking the key draws? Who are the defensive pairings in the final minute of a one-goal game?"

Labels: ESPN, Puck Prospectus

Monday, December 17, 2007

Starting in the NHL as a teenager does mean success

"Getting to the big time early doesn't necessarily mean you've made it big. Or to stay." - Damien Cox, ESPN.com, 12/12/07 in Starting in NHL as a teenager doesn't mean instant success.

Sometimes you run across something that's so illogical, it must be true. And Damien Cox's article on ESPN was one of those jarring ideas: young players who make it to the NHL before their 20th birthdays aren't necessarily guaranteed of a good career - and it takes years to know whether they'll be any good.

Cox presents what seems like plausible evidence: looking at the 1999 season, not every player who made the NHL as a teenager turned into a superstar. While this group included Vincent Lecavalier, Simon Gagne and Scott Gomez, it also featured Manny Malhotra, Brad Stuart, Martin Skoula, Rico Fata, Mathieu Biron, Artem Chubarov, Steve McCarthy, Oleg Saprykin and David Tanabe.

So Cox concludes: "There's no discernible trend, other than to say, based on that group of players, being in the NHL by 18 or 19 is no guarantee of future success."

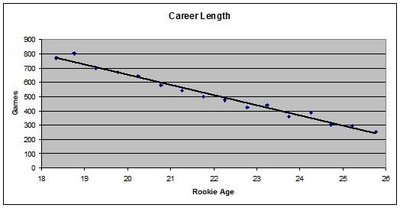

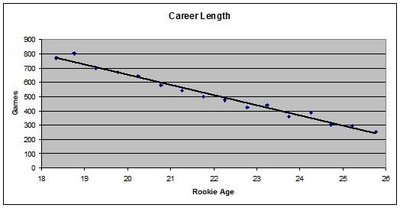

Well, maybe that's true, but let's extend our analysis beyond counting the number of "stars" in a single draft class and include every player who started his NHL career after 1967. Here we see the average career length based on a player's age on January 1st of his rookie NHL season:

The result is pretty clear: for every year older a player is when he debuts, he can expect to play 73 fewer games in his career. In other words, a 19-year-old rookie can expect to play until he's 29, and a 21-year-old rookie will also expect to play until he's 29. Starting late has no effect on when a player's career is over*.

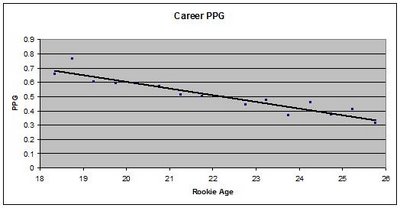

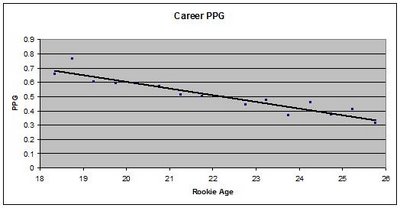

But maybe longevity doesn't translate to scoring prowess? We can use career points-per-game (PPG) to estimate offensive skill:

Again, the younger a player is when he starts out, the higher his rate of offensive production.

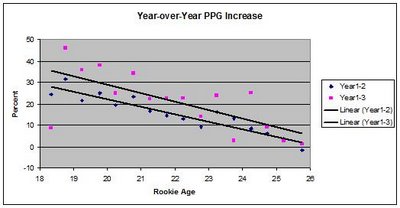

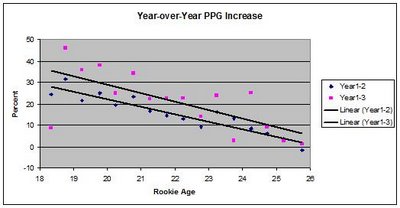

Well, what about Cox's assertion that it takes years for teenage rookies to establish themselves as good player? We can look at the year-over-year change in PPG for these players:

Again, the general trend is higher as a player gets younger: older players improve their skills less from year-to-year than younger ones. But we already knew that. It's true of 20-year-old juniors vs 18-year-old juniors, so why wouldn't it be true of 18- and 20-year-old pros?

Unfortunately, to claim otherwise, we need to take a leap based on a small amount of non-quantitative evidence. While there's no guarantee that teenage rookies will turn into superstars, the younger a player is on average when he makes the bigs, the better his career will turn out to be. However many high draft pick busts there are, they don't outweigh the huge number of successful players who hit the NHL in their teens.

* - The youngest age group, which was no older than 18 years and 3 months when the season starts actually performs slightly poorer than the group that's six months older. This is because of small sample size: all other groups include 6 months of birthdays, while this group only includes three months of player since they needed to be 18 on the day the season started. This group also includes Sidney Crosby and Patrice Bergeron, who will most certainly skew this group upwards as their careers progress.

Sometimes you run across something that's so illogical, it must be true. And Damien Cox's article on ESPN was one of those jarring ideas: young players who make it to the NHL before their 20th birthdays aren't necessarily guaranteed of a good career - and it takes years to know whether they'll be any good.

Cox presents what seems like plausible evidence: looking at the 1999 season, not every player who made the NHL as a teenager turned into a superstar. While this group included Vincent Lecavalier, Simon Gagne and Scott Gomez, it also featured Manny Malhotra, Brad Stuart, Martin Skoula, Rico Fata, Mathieu Biron, Artem Chubarov, Steve McCarthy, Oleg Saprykin and David Tanabe.

So Cox concludes: "There's no discernible trend, other than to say, based on that group of players, being in the NHL by 18 or 19 is no guarantee of future success."

Well, maybe that's true, but let's extend our analysis beyond counting the number of "stars" in a single draft class and include every player who started his NHL career after 1967. Here we see the average career length based on a player's age on January 1st of his rookie NHL season:

The result is pretty clear: for every year older a player is when he debuts, he can expect to play 73 fewer games in his career. In other words, a 19-year-old rookie can expect to play until he's 29, and a 21-year-old rookie will also expect to play until he's 29. Starting late has no effect on when a player's career is over*.

But maybe longevity doesn't translate to scoring prowess? We can use career points-per-game (PPG) to estimate offensive skill:

Again, the younger a player is when he starts out, the higher his rate of offensive production.

Well, what about Cox's assertion that it takes years for teenage rookies to establish themselves as good player? We can look at the year-over-year change in PPG for these players:

Again, the general trend is higher as a player gets younger: older players improve their skills less from year-to-year than younger ones. But we already knew that. It's true of 20-year-old juniors vs 18-year-old juniors, so why wouldn't it be true of 18- and 20-year-old pros?

Unfortunately, to claim otherwise, we need to take a leap based on a small amount of non-quantitative evidence. While there's no guarantee that teenage rookies will turn into superstars, the younger a player is on average when he makes the bigs, the better his career will turn out to be. However many high draft pick busts there are, they don't outweigh the huge number of successful players who hit the NHL in their teens.

* - The youngest age group, which was no older than 18 years and 3 months when the season starts actually performs slightly poorer than the group that's six months older. This is because of small sample size: all other groups include 6 months of birthdays, while this group only includes three months of player since they needed to be 18 on the day the season started. This group also includes Sidney Crosby and Patrice Bergeron, who will most certainly skew this group upwards as their careers progress.

Labels: ESPN, Projections

Subscribe to Posts [Atom]