Friday, February 6, 2009

More Gladwell (spoiler: he's wrong)

[This originally appeared in the "Committed Indian", the unofficial Chicago Blackhawks program...]

If you've got a friend in business - sales guy, MBA, doesn't matter - you've probably heard him talk about Malcolm Gladwell. Gladwell writes books about unintuitive things: his 2005 book Blink, was, if I recall correctly, about how thinking too hard on the job causes people to make more mistakes. Some of you might remember that line of thinking from Bull Durham. At any rate, Gladwell's most recent book, Outliers, is about how success is a combination of both talent and surprisingly more opportunity than we expected.

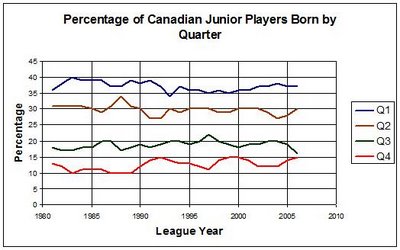

One outlier he identifies is the distribution of NHL players' birthdates: for decades, NHL players have been twice as likely to be born in the first three months of the year than in the last three. The reason why is fairly obvious - because little kids are divided into teams on the basis of what year they were born, the kids born earlier in the year are, on average, bigger and stronger and have almost an extra year of development. So they're the most likely to get picked by coaches focused on having the best team over the new few months. That leads to better coaching and competition and ultimately being more likely to get picked for a better team the next year.

This effect continues all the way through Junior hockey and the NHL, where the ratios of Q1 to Q4 birthdates are 3:1 and 2:1, respectively. Gladwell suggests that a lot of hockey talent is being squandered because professional players only started out a little bit better when they were kids but benefited tremendously from better coaching and competition. In an interview with ESPN, Gladwell said he suggested to officials from the Canadian national junior hockey team that they start a parallel league for kids born in the second half of the year, which would conceivably result in 150 additional NHL players if they equalized the first and second half birthdates. The officials supposedly told him it was "too complicated."

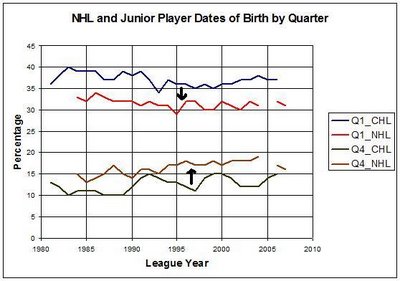

So splitting youth hockey into two leagues is too complicated even if it increases the number of players these leagues graduate to the NHL by 30%? If only it were so simple. The ratio of early-to-late birthdays is much higher in junior hockey than it is in the NHL, and so while the player development process may favor the older players from age 5-18, the jump from junior hockey to the NHL actually favors players born later in the year.

It's not surprising either - a player like Patrick Kane, who was born at the end of December, suddenly gained an extra year of development compared to a player who was born in January of the same year. And, after all those years playing in leagues where coaches were only concerned with how good you were going to be this season, the NHL is really only concerned with how good you're going to be at your best, which is usually when you're in your early-to-mid-20s. Even without the extra season, if you have two players with identical statistics in junior hockey, the December player projects to score 50% more points in the NHL than the player born in January, largely because he's put up those points against competition that's relatively bigger and stronger than he is.

Now remember that we're talking about all NHL players, including anyone who plays in even just one game. If we only look at former Canadian junior players who were in the top sixth in NHL scoring, which was anyone with 42 points or more last year, the ratio of early-to-late birthday players over the last decade is about 1.20:1. If we managed to equalize these two groups over the course of the next 25 or 30 years, that would ultimately add about seven Canadian players to the top sixth of the league. That's nothing to sneeze at, but it's not as if, as Gladwell suggested, we're "squandering the talents of hundreds of boys with late birthdays" by not doing so. It turns out that the group where players with early birthdays are most over-represented is the league leaders in penalty minutes per game, and I can't see anyone getting up in arms about whether some kid's December birthday kept him from becoming the next Ogie Ogilthorpe.

If you've got a friend in business - sales guy, MBA, doesn't matter - you've probably heard him talk about Malcolm Gladwell. Gladwell writes books about unintuitive things: his 2005 book Blink, was, if I recall correctly, about how thinking too hard on the job causes people to make more mistakes. Some of you might remember that line of thinking from Bull Durham. At any rate, Gladwell's most recent book, Outliers, is about how success is a combination of both talent and surprisingly more opportunity than we expected.

One outlier he identifies is the distribution of NHL players' birthdates: for decades, NHL players have been twice as likely to be born in the first three months of the year than in the last three. The reason why is fairly obvious - because little kids are divided into teams on the basis of what year they were born, the kids born earlier in the year are, on average, bigger and stronger and have almost an extra year of development. So they're the most likely to get picked by coaches focused on having the best team over the new few months. That leads to better coaching and competition and ultimately being more likely to get picked for a better team the next year.

This effect continues all the way through Junior hockey and the NHL, where the ratios of Q1 to Q4 birthdates are 3:1 and 2:1, respectively. Gladwell suggests that a lot of hockey talent is being squandered because professional players only started out a little bit better when they were kids but benefited tremendously from better coaching and competition. In an interview with ESPN, Gladwell said he suggested to officials from the Canadian national junior hockey team that they start a parallel league for kids born in the second half of the year, which would conceivably result in 150 additional NHL players if they equalized the first and second half birthdates. The officials supposedly told him it was "too complicated."

So splitting youth hockey into two leagues is too complicated even if it increases the number of players these leagues graduate to the NHL by 30%? If only it were so simple. The ratio of early-to-late birthdays is much higher in junior hockey than it is in the NHL, and so while the player development process may favor the older players from age 5-18, the jump from junior hockey to the NHL actually favors players born later in the year.

It's not surprising either - a player like Patrick Kane, who was born at the end of December, suddenly gained an extra year of development compared to a player who was born in January of the same year. And, after all those years playing in leagues where coaches were only concerned with how good you were going to be this season, the NHL is really only concerned with how good you're going to be at your best, which is usually when you're in your early-to-mid-20s. Even without the extra season, if you have two players with identical statistics in junior hockey, the December player projects to score 50% more points in the NHL than the player born in January, largely because he's put up those points against competition that's relatively bigger and stronger than he is.

Now remember that we're talking about all NHL players, including anyone who plays in even just one game. If we only look at former Canadian junior players who were in the top sixth in NHL scoring, which was anyone with 42 points or more last year, the ratio of early-to-late birthday players over the last decade is about 1.20:1. If we managed to equalize these two groups over the course of the next 25 or 30 years, that would ultimately add about seven Canadian players to the top sixth of the league. That's nothing to sneeze at, but it's not as if, as Gladwell suggested, we're "squandering the talents of hundreds of boys with late birthdays" by not doing so. It turns out that the group where players with early birthdays are most over-represented is the league leaders in penalty minutes per game, and I can't see anyone getting up in arms about whether some kid's December birthday kept him from becoming the next Ogie Ogilthorpe.

Labels: Committed Indian, Gladwell, junior hockey

Thursday, December 11, 2008

Malcolm Gladwell's Outliers and making the NHL

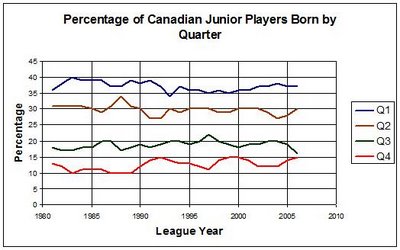

In his book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell discusses the odd distribution of birth months among NHL players. Because youth players are registered in leagues based on their year of birth, the biggest and strongest players tend to be those born in the first few months of the year. This selection process starts as early as age 8, and the effect persists more than a decade later in junior hockey in Canada. The effect has been visible for decades:

One thing that's very unintuitive about this effect is that, other things being equal, if you have a 17-year-old player who puts up the same number of points as an 18-year-old player, the 17-year-old will have a much higher performance ceiling. I like to call this the 'Wayne Gretzky-Dan Hodgson' effect - two players who had identical stats their last year in junior; but Gretzky was 16 and Hodgson was 19, and so it was obvious who would have the better NHL career.

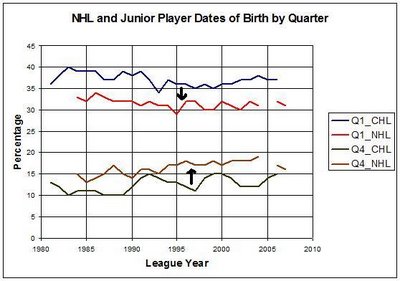

At any rate, if you have identical junior players born in January and December, the December player was almost a year younger when he achieved his performance. If we project that performance forward to Age 23, then we'd expect the December player, on average, to be better. And this is an effect we see when we compare the birthdates of junior hockey players to NHL players:

The first time that players aren't strictly grouped by birthdate is when they reach professional leagues. At this point, younger players outperform older players by a wide margin, making the jump from junior hockey to the NHL at a 50% higher rate. Gladwell mentions in his ESPN interview that "Canada is squandering the talents of hundreds of boys with late birthdays." It seems pretty clear that he's right.

One thing that's very unintuitive about this effect is that, other things being equal, if you have a 17-year-old player who puts up the same number of points as an 18-year-old player, the 17-year-old will have a much higher performance ceiling. I like to call this the 'Wayne Gretzky-Dan Hodgson' effect - two players who had identical stats their last year in junior; but Gretzky was 16 and Hodgson was 19, and so it was obvious who would have the better NHL career.

At any rate, if you have identical junior players born in January and December, the December player was almost a year younger when he achieved his performance. If we project that performance forward to Age 23, then we'd expect the December player, on average, to be better. And this is an effect we see when we compare the birthdates of junior hockey players to NHL players:

The first time that players aren't strictly grouped by birthdate is when they reach professional leagues. At this point, younger players outperform older players by a wide margin, making the jump from junior hockey to the NHL at a 50% higher rate. Gladwell mentions in his ESPN interview that "Canada is squandering the talents of hundreds of boys with late birthdays." It seems pretty clear that he's right.

Labels: Gladwell, junior hockey

Subscribe to Posts [Atom]